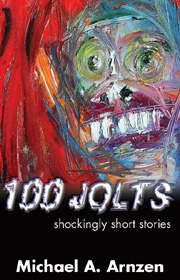

April/May 2004

The Beauty of Flash

The popularity of the internet and PDAs has increased the demand for short fiction.

But shorter is not necessarily less according to author Michael Arnzen, "Minimalist horror is a shotgun shell: a tightly wadded package of shrapnel designed for maximum coverage, minimal escape."

Preorder now at Shocklines.com.

"I like flash fiction that makes the most out of the brevity of the form—not long stories masquerading as short ones, but fiction that exploits the limitations of space."

Arnzen points out that the horror story offers fertile ground for flash creators. "Horror is the genre of the jolt, the shock, the spark. The horror story’s conflict is always a matter of life and death, but death...almost always comes too soon—that’s why we fear it. Life is always too short."

Arnzen's flash breathes new life into a decaying genre, "100 Jolts delivers far more than is promised by its title; with this magnificent collection of literate and disturbing short-shorts, some which are among the darkly funniest I've ever read....This book is a remarkable achievement." —Gary A. Braunbeck, author of In Silent Graves

"Simply stated, there's nothing like this collection of ultra-short fiction. Arnzen continually impressed me with his punchy narrative style and endless images of grue, gore, and gristle. An evening with this book will leave you feeling like you've been gutted like a dead fish and hung out to dry." —Tom Monteleone, author of The Blood of the Lamb

An Ounce of Brains

by Michael

A. Arnzen

Jimmy returned from his trip to the hardware store with a six pack

of Corona and a spool of plastic tubing. He immediately set to work,

chugging three of the Mexican beers and rigging one end of the tube

to the lip of plastic jug he'd already cleaned and sterilized. After

a fourth beer, he felt anesthetized enough to clip the other end of

the tube to give it a sharp point and then run it into his right nostril.

Hand over hand, he slid it up past the sinus that sphinctered and

wheezed wetly around the plastic, and Jimmy grinned when the jug fogged

with his breath, proving he'd made a tight seal. This egged him on

as the tube caught for a moment against the back wall of his sinuses

-- a dull knock against the door to his brain, somewhere behind his

eye sockets -- and with one big shove he pushed it through the membrane

and into the stringy fibrous underside of his cerebrum. The penetration

felt something like pressing a fork into steel wool: its net of neurons

gave little passage, but it was stuck in the mesh nonetheless.

He waited for the ideas to come pouring out.

A few hours later, the jug was so full, the yellow goop of his thoughts

ran up the catheter like gas in a siphon straw. When he slid the tubing

out of his head, some of this overspill pissed out of the tube and

onto his lap. Jimmy never felt so clear, so renewed -- so free to

pursue new thoughts to bank into the new aporia s he'd opened inside

his head.

He grabbed his jug of thoughts and a bottle of vodka and went to school.

In class, he inhaled every word that came out of a professor's mouth,

as though sucking it right through his nose and into the spongy tissue

of his brain. By the end of the day, he'd stockpiled enough ideas

to siphon out the following day. But in the mean time, he set up a

little shop outside the administration building, selling brain shots.

It was midterms; they sold out quickly.

After several weeks of this routine, the job began to take its toll

on him. The demand was getting high and he only had so much brains

to spare. In an accounting class, he let his mind drift toward thoughts

of getting a partner or taking out a want ad. But as he watched the

teacher drone on and on about finances, he found himself staring at

the man's large nostrils, and realized the solution to his problem

had been staring him in the face all along.

After school that day, he returned from the hardware store with six

spools of tubing. And a lead pipe. And a faculty directory.

The teachers resisted at first, naturally, but when he opened their

minds they saw his brilliance. They gave him a scholarship in entrepreneurial

studies. And they eventually sent him to graduate school to harvest

the spoils of his success.

But graduate students were more refined, more cultured. They didn't

appreciate his crass commercialism at all. They wanted brandy with

their brains, not cheap vodka. And they wouldn't have any of his new

ideas that hadn't been aged and fermented in oak barrels. But the

extra effort these snobs demanded of him balanced out in the end.

For despite their better brains, when they raised their noses, they

made his job far easier than they knew.